![]()

Write us!

socialistviewpoint@pacbell.net

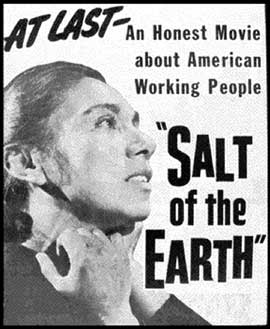

Blacklisted Film Restored and Rehabilitated

By Lee Hockstader

It is doubtful that any other American movie ever inspired such official harassment and outright intimidation as “Salt of the Earth,” the saga of striking Mexican American miners written and directed by blacklisted Hollywood filmmakers during the Red Scare. During the course of production in New Mexico in 1953, the trade press denounced it as a subversive plot, anti-Communist vigilantes fired rifle shots at the set, the film’s leading lady was deported to Mexico, and from time to time a small airplane buzzed noisily overhead.

It is doubtful that any other American movie ever inspired such official harassment and outright intimidation as “Salt of the Earth,” the saga of striking Mexican American miners written and directed by blacklisted Hollywood filmmakers during the Red Scare. During the course of production in New Mexico in 1953, the trade press denounced it as a subversive plot, anti-Communist vigilantes fired rifle shots at the set, the film’s leading lady was deported to Mexico, and from time to time a small airplane buzzed noisily overhead.

The plane’s buzzing played havoc with the soundtrack, moving the producer, Paul Jarrico, to wisecrack: “We’ll make this picture again sometime. And next time we’ll say, ‘You’ve seen this great picture. Now hear it.’”

“Salt of the Earth” was completed eventually, only to be so thoroughly suppressed on its release in 1954 that some film historians call it the only blacklisted American movie.

But “Salt” had a second act. The back-story of its suppression, as much as the movie itself, inspired a cult following of leftists, feminists, Hispanics, historians and film buffs. They rediscovered it in the 60s and resurrected it gradually in film schools, union halls and women’s centers. And having sustained it for 50 years, “Salt’s” fans converged by the hundreds over the weekend here for a conference that was part tribute to the film and part political protest rally.

As the theater lights dimmed for a showing of “Salt” on the conference’s opening night, Dolores Huerta, the renowned labor leader who, with Cesar Chavez, founded the United Farm Workers, cried, “Viva la justicia!”

Sponsored by the College of Santa Fe, the conference was dedicated to the proposition that the film’s message of self-empowerment, and the act of political dissent its production represented, are as relevant in terrorism-obsessed 21st-century America as they were in the communism-obsessed America of the McCarthy era.

To the film’s loyalists, the fact that Hollywood is planning a remake of “Salt of the Earth” is proof of its resonance. In a new age of threats from abroad, the suppression of “Salt of the Earth” was taken as an object lesson of the perils of intolerance and shrinking civil liberties.

“I’m not making the comparison to McCarthyism, but I do think that under cover of creating an atmosphere of war, government can overreach and take power and limit people’s freedom and rights in ways that could not occur were it not for this atmosphere of fear,” said Moctesuma Esparza, who is producing the remake of “Salt of the Earth.” Esparza, who produced “The Milagro Beanfield War” and “Gods and Generals,” expects filming on the remake of “Salt” to begin later this year.

The original film was the brainchild of director Herbert Biberman, who had been jailed for refusing to cooperate with the House Un-American Activities Committee; Michael Wilson, a talented screenwriter who later wrote “The Bridge on the River Kwai” and “Lawrence of Arabia”; and Jarrico. Denied work in Hollywood studios because of their Communist affiliations, the three formed an independent production company. They decided to make a film dramatizing the 1950-51 strike at the Empire Zinc Mine in southwestern New Mexico.

Or, as Becca Wilson, daughter of screenwriter Wilson, put it at the conference: “They decided to commit a crime equal to their punishment.”

Seen through a contemporary lens, the movie’s story line is tame enough: The little guys—denied fair wages, decent housing and safe working conditions—take on the big guys, and the little guys win. But there were twists. For starters, the little guys were Mexican Americans, a group much more marginalized in the mid-1950s than now. And when a court ruling ordered them off the picket line, their wives and sisters took their places, in some cases defying their macho husbands.

Financing for the film came largely from the Mine-Mill Union, whose Local 890 had led the strike. The filmmakers consulted extensively with the miners on the script and used many of the miners themselves in the cast. Among them was the male lead, Juan Chacon, who happened to be president of Local 890.

Playing a tough miner, Chacon stands up to the callous Anglo bosses. He gets beaten up and thrown in jail for his trouble. When he is enjoined from picketing, his wife, played by Mexican actress Rosaura Revueltas—deported because of visa technicalities before the end of filming—steps into the fray. Their marriage is strained but survives.

From the start, “Salt” inspired animosity. The Hollywood Reporter called it “commie” propaganda directed by the Kremlin. A Republican congressman, speaking on the floor of the House, vowed to keep “this Communist-made film” out of the movie theaters.

The FBI scrutinized the film’s financing, seeking a Communist Party connection. (There was none.) The American Legion called for a boycott. Processing labs were ordered not to handle the film. Unionized projectionists were instructed not to show it. The film, edited in secret, was stored for safekeeping in an anonymous wooden shack in Los Angeles.

Against all odds, “Salt” opened in New York. The miners, for whom a screening was arranged in New Mexico, were pleased. But when the film tried to move on to Chicago, Detroit and elsewhere, theaters refused to show it. Disheartened, Jarrico moved to Paris. His Independent Productions Co., which had made plans for several more films, was dead.

“Salt of the Earth” was “one of the most kamikaze political actions they could ever have done,” said David Wagner, a film historian specializing in the blacklist who is co-author of “Radical Hollywood,” published last year.

Nonetheless, the movie was a hit in Europe, opening to critical acclaim and winning prizes at film festivals in Paris and Czechoslovakia.

“We were in France when we first saw it, and I’ll never forget the lines around a small cinema on the Left Bank—four people abreast around and around the block,” said Norma Barzman, a blacklisted screenwriter who had left the United States and was living in Paris.

For more than a decade, few people saw the movie in the United States. But in the 1960s, “Salt” began to gain an underground following. During an epic strike against grape growers in the mid-60s, the United Farm Workers began showing the film to inspire its embattled membership.

“I probably saw it a dozen times at least,” said Huerta, the UFW founder. “They’d show it on Friday nights, and seeing that film was a great morale booster.”

The zinc mine that was the site of the strike closed in 1967. But curiosity about the movie grew. Left-leaning film schools began teaching it. In 1992 the Library of Congress decreed that a print of “Salt” would be kept for all time. The Museum of Modern Art in New York preserved it. In Silver City, N.M., near the old mining town of Bayard, where the original strike took place, the local video store kept two copies of the movie, which it lent out free of charge.

There was also an afterlife for the miners and their wives who took part in the strike and, in many cases, the movie. The gains they had made in the strike were significant. In addition to securing better pay, they had ended a discriminatory system in which Hispanic miners were barred from safer above-ground jobs and denied indoor toilets and running water in company-owned housing. And they had memorialized their own achievements in the movie.

“The company figured they’d starve us in two months and we’d be back to work—it never happened,” said Lorrenzo Torrez, 75, a retired miner who took part in the strike and the movie. “We earned a lot of respect. After that the police in New Mexico”—who had intervened on the side of management—“kept out of strikes. They decided it was between the union and the workers.”

James Lorence, a historian at Gainesville College in Georgia, discovered “Salt” in the mid-1980s and began teaching it in his classes. He was struck by the enthusiasm his students felt for such an old movie, and he wrote a history of the film, “The Suppression of ‘Salt of the Earth.’”

“It resonates as an icon with feminists, it resonates in the Chicano movement,” he said. “In a sense, Wilson, Biberman and Jarrico had the last laugh.

—Washington Post, March 3, 2003

Write us

socialistviewpoint@pacbell.net